[Originally published as “Bark Blankets and ‘Esquimaux Implements from Alaska’: Revisiting a Historic Oberlin-Smithsonian Exchange” by Amy V. Margaris. Smithsonian Institution Arctic Studies Center Newsletter, Issue 24, May 2017, pp. 45-48.]

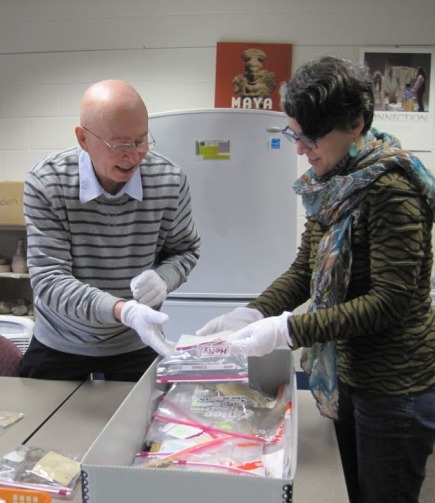

As curator of the Smithsonian’s circumpolar ethnology materials, Igor Krupnik is intimately familiar with the collections obtained by some of the most famed Arctic naturalists of the 19th century. But the last thing he expected to see during a recent trip to Oberlin College in northeast Ohio was a portion of those collections stored in a big box in my Anthropology Lab.

Igor and I met in April 2016 when he came to campus to participate in a panel on indigenous peoples and climate change. We shook hands, and I mentioned that a colleague and I had been researching some interesting Arctic material that he might want to take a look at. Later that day we unboxed the 36 ethnological objects which Igor was astonished to learn are associated with four of the Smithsonian’s greatest pioneers of Arctic science and anthropology: William Healey Dall, Lucien Turner, John Murdoch, and Edward William Nelson.

William Dall was the earliest of the group, and at the end of a long table we carefully placed a painted wood tray and ladles from his pioneering 1860s voyage up the Yukon River into Alaska’s interior. Their original National Museum exchange labels are still legible: “Ingalek Esqmx.” Other objects in Oberlin’s Arctic collection were obtained in the era of the first International Polar Year (1882-1883) when Spencer F. Baird was Smithsonian secretary. Baird helped guide a number of naturalists onto IPY projects in Alaska and the eastern Canadian Arctic where they collected meteorological data and, on the side, worked to obtain cultural and natural historical specimens on behalf of the Smithsonian.

Dall later helped outfit a rookie Lucien Turner for his first Alaskan voyage, to the busy fur trade center of St. Michael (1874-77). Turner then spent the years 1878-1881 acquiring specimens in the Aleutians, and in 1882-1884 joined an expedition to the Fort Chimo (now Kuujjuaq) IPY station on eastern Canada’s Ungava Bay. Turner somehow found time to fulfill his prescribed meteorological duties at Fort Chimo while also amassing enough material culture documenting the local Innu and Inuit peoples’ ways of life to produce the 1894 monograph, The Ethnology of the Ungava District, Hudson Bay Territory (reissued in 2001 with an introduction by ASC anthropologist Stephen Loring). Oberlin has six of Turner’s acquisitions representing each of his three scientific expeditions, including a carved ivory doll from Norton Sound, a seal gut sack from Unalaska (“Unalashka”), and a charming pair of snow goggles collected in “Mugara Labrador.”

Next out of the box was an iron-bladed knife with an antler handle inked with the name “P. H. Ray.” Lieutenant Ray led the IPY station at Alaska’s Point Barrow and purchased over 1500 pieces of manufacturing and hunting equipment from Inupiat hunters who visited the station. However, it was the Baird-trained naturalist on the expedition, John Murdoch, who eventually documented the enormous collection in his lengthy 1892 BAE report, Ethnological Results of the Point Barrow Expedition.

Most of the remaining objects now spread across the table were obtained by the famed Edward Nelson. (The other four were collected by I. Applegate, C. L. McKay, and Lieutenant G. M. Stoney.) Nelson began as Lucien Turner’s Signal Corps replacement at St. Michael (1877-81) but ventured far off the Corps’ beaten path during his excursions to document the natural history and peoples of the western Arctic. His extraordinary collection of roughly 10,000 cultural objects was complemented by photographic glass plates, field journals, and linguistic materials that help document the lives of the Yup’ik and other peoples with whom he interacted.

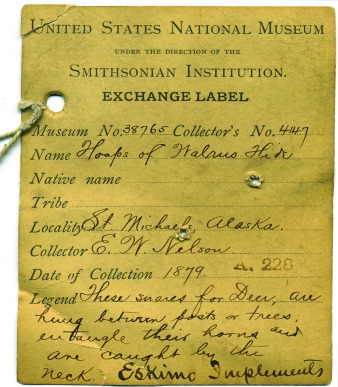

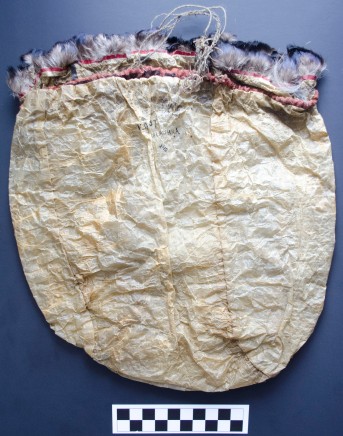

Igor and I shared a laugh at how Nelson’s Yup’ik trading partners famously dubbed him “the man who collects good-for-nothing things”: the very netting shuttle pictured (LXXIII Fig. 26) in Nelson’s classic 1899 monograph The Eskimo About Bering Strait (reprinted in 1983 with an introduction by ASC director William Fitzhugh); a yaaruin, or storyknife, used by Yup’ik girls to scratch stories in the snow; hoops of walrus hide. As we reverently laid each object out for inspection, we mused that these were mostly workaday objects that were never intended to outlast their makers. Yet here they were – roughly 125 years after leaving the North – everyday things elevated to the extraordinary as documentation of 19th century Arctic peoples’ ways of life, and as testaments to the remarkable work of four famed Arctic scientists.

So how did these Arctic treasures become associated with a small liberal arts college in the Midwest? Linda Grimm, now Professor Emerita of Oberlin’s Anthropology Department, and I have delighted in tracking down much of the story. (A fuller version can be found in Margaris and Grimm 2011).

We begin with the fact that in the mid-19th century, any U. S. college or university worth its salt needed a natural history cabinet. Science education was (thankfully) moving away from rote learning and recitation to a hands-on approach using specimen-guided laboratory instruction. By the 1880s the cabinet of teaching specimens at Oberlin College had grown from a medley of mostly donated specimens to a full-fledged museum – complete with letterhead stationery – and administered by the forward-thinking geology and natural history professor, A. A. Wright.

Much of what we know about the Oberlin College Museum today comes from Wright’s museum accession book and correspondence preserved in the Oberlin College Archives. Together they document the wide network of scientists, locals, and Oberlin alums that Wright used to grow the college’s systematic natural history collections. We know that Wright followed Spencer Baird’s lead in using specimen exchanges to help acquire diverse teaching collections, and by the early 20th century the Oberlin College Museum was home to thousands of zoological, botanical, and mineralogical specimens. Wright even employed a skilled student assistant in the museum, Lewis M. McCormick, who was eminently qualified – having worked as a taxidermist and osteologist at the Smithsonian’s National Museum before enrolling at Oberlin in 1885.

Wright also corresponded with Oberlin alumni missionaries and teachers abroad requesting donations of cultural material. One of these, the Reverend Erwin Hart Richards (b. 1851—d. 1928) was able to supply Oberlin’s museum with hundreds of ethnological objects from Thonga communities in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique) and the Zulu of South Africa. We’ve uncovered no documentation of the ethnology materials’ use in teaching, however, and Oberlin College did not offer regular courses in anthropology until the 1940s. The evidence instead suggests that A.A. Wright valued Oberlin’s ethnology collections primarily as “currency” that he could exchange for items that would contribute more directly to the school’s teaching mission in the natural sciences. Indeed, the Richards collection from Africa caught the eye of the National Museum, whose own holdings were much more focused on the Americas. In 1888-89 Oberlin and the Smithsonian exacted an exchange.

Oberlin sent 89 African objects to Washington in 1888 including 28 bark blankets, 12 circumcision sticks, and one xylophone. (Their images can now be found on the Smithsonian Anthropology Department collections database, thanks to the work of recent Oberlin Anthropology major and 2014 Smithsonian intern Victoria Costikyan.)

Interestingly, 125 years before Victoria’s trip to the National Museum, another Oberlin student made that same journey: A.A. Wright’s assistant and former Smithsonian insider, Lewis McCormick. McCormick used his time and talents to select choice zoological and geological specimens for the college. He also helped “close the [Oberlin’s] account” with Otis Mason’s ethnology department by sending Oberlin 73 ethnological specimens, including a lot of “45 Esquimaux implements” (as recorded in our museum accession book) obtained by Nelson, Turner, Dall and Ray. The size of the lot and its association with these Arctic greats made it much more significant than the typical “starter kits” the National Museum occasionally sent to other small institutions. Yet we know little about what happened to this special Arctic collection after Oberlin received it in 1889.

The Oberlin College Museum closed in 1959 and its various cultural and natural history collections were left “dangling” without formal curatorship and institutional buy-in. Deemed out of date in light of new scientific modes of inquiry, the collections were shunted from building to building and eventually parceled out to relevant departments – a sadly typical story of demise for campus museums of the era. Eventually the ethnology collections were relegated to a pair of custodial closets where they sat basically undisturbed and unused for decades.

Recently I’ve been reminded of the famous 19th century painting by Charles Willson Peale that shows the artist and naturalist pulling back a curtain to reveal a series of wondrous natural treasures, each neatly arranged in his eponymous museum. The timing of Igor’s visit to Oberlin couldn’t have been more fortuitous because the college is in the process of “lifting the veil” from many of its own historical treasures. Linda Grimm and her students kick-started the process in the early 2000s when they created an online database for much of Oberlin’s roughly 1600-object ethnographic collection (http://www.oberlin.edu/library/digital/ocec/) which highlights our Richards collection from Africa and will soon include our Arctic material.

Today we can account for 36 of the Arctic objects obtained in the 1888-89 Oberlin—S.I. exchange. Most are in excellent condition but a few, such as the three bags constructed of fish skin or gut, need significant conservation work to help restore their delicate tissues, feathers, and other decorative details. Current Oberlin students Cori Mazer and Alice Blakely are researching Oberlin’s Arctic collection for inclusion in our ethnographic collection database and an eventual campus exhibition – two ways to begin breathing new life into these once closeted treasures. We hope this newsletter article will bring further attention to Oberlin’s valuable Arctic materials, and more broadly, to the vast but largely underdeveloped teaching and researching potential of the historical “dangling collections” that are found on so many of our nation’s college campuses.

Oberlin is extremely fortunate that the College plans to move our entire ethnographic collection to new custom storage in our main library where it can be readily accessed for teaching and research. While that process unfolds, an interdisciplinary group of faculty and staff is working to develop a unified database of our many teaching objects that are scattered throughout the campus, including those once part of the Oberlin College Museum.

In this same spirit we can now begin to envision a centralized web space for Edward Nelson’s vast but widely dispersed ethnology collections – a sort of digital family reunion where objects that are physically disseminated across many institutions, including Oberlin and the Smithsonian, could be reassembled for cohesive study. “Nelson in the cloud” holds the promise of helping source communities become reacquainted with these old friends, and contributing to a wider understanding of the uses and meanings of these special objects.

Further Reading

Margaris, Amy V. and Linda T. Grimm. 2011. “Collecting for a College Museum: Exchange Practices and the Life History of a 19th Century Arctic Collection.” Museum Anthropology Vol. 34(2):109–127.

Amy Margaris is Associate Professor of Anthropology at Oberlin College and de facto curator of the Oberlin College Ethnographic Collection. She teaches and publishes in the areas of archaeology, colonialism, museum studies, and material culture analysis.